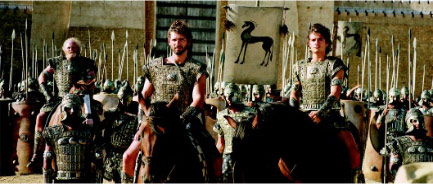

David Benioff's Epic Adaptation, TROY

June 1st, 2004

I couldn’t imagine the daunting task of adapting a work like The Iliad to the movie screen, but at the age of 34, David Benioff has already adapted Homer’s The Iliad and is now working on the screenplay for Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. It’s a good thing all those writers are dead. Otherwise, Benioff might feel some pressure.

Benioff’s work first hit theatres when Spike Lee had him adapt his own novel, The 25th Hour, for him to film. The film received wide critical praise. But already, Benioff was in the weeds with writing his multiple drafts of Troy. It’s unusual for a $200 million production to only use one writer, but Benioff worked closely with director/producer Wolfgang Peterson and even worked with Brad Pitt on making his character of Achilles more human.

Besides The Iliad what sources did you draw on?

Of course there are more source texts than just The Iliad. I mean The Iliad was the pivotal one in the telling of the Trojan War, but it starts from the ninth year of the war and ends in the ninth year of the war. We wanted to tell the entire story from before the beginning when Paris seduces Helen and triggers the entire war through to the fall of Troy, and you don’t get all of that in The Iliad, so some of it comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and some of it comes from The Odyssey, actually. There are little bits from Eneid. There are bits of things from Bulfinch’s Mythology, and some of it was just imagined.

Was there a tendency not to write too contemporary?

Yeah, that’s one of the big challenges in screenplays. You don’t want the characters to sound contemporary. You don’t want them to sound like California boys in 2004, but at the same time it won’t work effectively if they sound exactly as they do in Homer because Homer is not really dialogue. It’s more of these dueling monologues, which are beautiful, but they are at least ten minutes long.

Agamemnon will launch into this long speech, and Achilles will respond with his very articulate rebuttal, and it just goes on. I don’t really want to sit there watching one character make a speech for 15 minutes and then have the next one do the same. It’s trying to find some kind of happy medium between contemporary lingo and the Homeric, ultra-exalted dialogue.

How many writers had their fingers in the screenplay?

I was the only writer the whole time. It started with the pitch that I made, and I was lucky enough to not be replaced, which I’m incredibly happy about; I would’ve been heartbroken, and it happens most of the time. So it’s partly luck and I think partly because [director] Wolfgang [Peterson] and I work well together.

When I started the screenplay, I had no idea it was going to be a $200 million movie. I think that would’ve been incredibly intimidating because this was only the second script I wrote. I was kind of dumb about the whole thing. I mean I didn’t really get nervous until after I had written it. I didn’t really understand how intimidating it was until I actually went on set and saw the size of these sets and saw the thousands of extras running around. It was a massive undertaking.

How do you pitch a faithful retelling?

Well, I didn’t pitch a faithful retelling. I pitched kind of a ruthless retelling where I really wanted to concentrate on the human story. For me, what I’ve always loved about The Iliad is the story of Hector, Achilles, Paris and Helen but particularly Hector and Achilles. These are the two great heroes on either side, and inevitably, they are going to fight, but it’s not a good-guys-and-bad-guys story. It’s not the epic battle of good versus evil. It’s not humans versus orcs. It’s humans fighting humans, and that’s why I think it’s the great tragic war story. Every time you see a soldier fall, it’s not some villain falling. It’s a human. It’s some mother’s son, and that’s what’s brilliant about Homer’s telling of the story. Each time, he always gives you one moment with that character, even very minor characters you’ve never met before, at the moment of their death. It’s a very humanistic way of telling a war story.

When you sat down to write this story, did you have the talent in mind?

I did not, and actually I’m glad of that because it would be hard for me. It is harder for me to write knowing the face in some ways because then you tend to write for the actor, and I really wanted to just let the characters exist in my imagination or the characters from the original text. I’m not writing lines for Peter O’Toole or for Brad Pitt or Eric Bana but for Priam, Achilles and Hector. Why did you change the way Agamemnon died? The ruthlessness is there. In the myths, Agamemnon can’t get the right winds to get to Troy, so he sacrifices his daughter, and this irritates his wife. So at the end of the war, when he sails home, his wife ends up killing him. We didn’t have time to tell all the different stories. My first draft of the script came in at 180 pages, which is a monster script, and there still wasn’t a way to tell all the different strands. Eventually, it was cut to 140 pages, and there was a certain ruthlessness involved. We had to pick the stories that we could follow all the way through. If we weren’t going to have the whole story of Agamemnon and his daughter and his wife, we had to figure out a way we could allude to his death the way that it’s depicted in the myth. He was knifed by a woman, so that was the way it was handled there, but there were certain changes made, sometimes for efficiency and sometimes because I had to choose what I thought was best for the movie. As for being absolutely faithful to the source material, I’m always going to pick the project.

Were there any other endings?

Yeah, from the original pitch, it was meant to be the story of Achilles and Hector, these two great heroes. Hector is killed 25 or 30 minutes before the end, and then Achilles is killed. Once your two main guys are dead, there’s not much more story to tell there. I think we could have an eight-hour miniseries that goes through all the different phases of the characters, but if you’re going to try to do it as a feature, you really have to cut many different things. The ending we have now was pretty much always the ending, and we are lucky in that we have Sean Bean doing that final voiceover with his magnificent voice. This is a tragic story in many ways, and I love the image of the ending with the smoke rising to the skies. I don’t know if that was originally in the script or if it was Wolfgang’s idea.

Was it a coincidence that Brian Cox was in two films you wrote, The 25th Hour and now Troy?

Total coincidence. I mean, when they were looking for Agamemnon, I remember talking to Wolfgang about what a marvelous actor I thought he was, and Wolfgang was already aware of him. It ended up being a happy coincidence for me because I just thought he was terrific and loved him as James Brogan in The 25th Hour.

What was it like working with Wolfgang?

He’s got this remarkable stamina, which he absolutely needed to direct this movie because it’s such a massive undertaking. There were constantly crises going on. It was not the easiest shoot, and he’s up everyday. He gets up and goes to work to oversee this giant enterprise. When we met, we probably spent 80 hours in his office going over the script, and by the end he knew that script better than I did. He could say, “This line is a problem on page 82,” without having the script in front of him, and I would have no idea what he was talking about. I would flip to page 82, and there’s the line. We spent an incredibly large amount of time together, and he was very fatherly. He was very warm, and again, I’ve been lucky that I’ve been able to work with some really wonderful directors though they’re all very different in their own ways. This is the man who did Das Boot, which is one of my favorite war movies, so it was great to have him doing this one. How many changes were made from the actual script? I went through maybe 30 different drafts. I think the first draft was turned in January of 2002, and they started shooting in April of 2003. On my computer I’ve got the Troy folder with literally 32 different drafts, and it’s kind of funny because you’ll see the first draft and the second draft are very different. Then, maybe by the 10th draft, it’s kind of closer to the first again.

Was it mind numbing?

I don’t think I ever got numbed from it, but it is a danger because, when you read the same pages so many times, sometimes you need to have a different opinion. Sometimes it’s actually helpful getting an actor in who’s playing the part to sees it in a different light. Some screenwriters dread getting notes from actors, and maybe at some point I will also dread it, but right now it’s actually interesting to get their opinions.

Why is the Troy legend still popular?

The story is 3,000 years old, and it’s constantly relevant. There is always a war going on somewhere in the world, and I don’t think there’s ever been a better war story told.

Do you think it’s particularly relevant now considering what’s going on with Iraq?

This could be relevant if it came out 20 years ago. I think it is eerie though when you see the shots of Achilles dragging Hector behind his chariot in light of what happened in Fallujah. But I wrote the script way before the Iraq war, and I was never consciously trying to map on current events to this story.

You are doing an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls. What’s the difference between that and doing Troy?

Luckily, those writers are both dead, so I don’t have to deal with that. I’ve also just adapted a living writer who I’m actually friendly with named George Pelicano. In some ways that’s more pressure because Pelicano can email me if he’s unhappy with the script, and those guys can’t. I think one big challenge with the Hemingway is that it’s set in Spain and the book is written in English, but we’re supposed to understand that they’re speaking Spanish. So when a Spaniard says, “Oh your English is so good,” it’s a little confusing. I’m getting confused just talking about it, but one thing that is interesting about the two is that they’re both war stories and both writers take care to show that it’s not good versus evil.

Is it a greenlit script?

I don’t know if anything’s really greenlit until they start. Chris Nolan is attached to direct it, but he’s in the middle of Batman Begins.

What are the most telling pieces of dialogue in Troy?

For me my favorite scene is the scene between Priam and Achilles with Peter O’Toole and Brad Pitt. It’s the last scene in the Iliad, and it’s one of the most heartbreaking scenes in literature. It’s kind of great because writing lines and having them spoken by Peter O’Toole is an amazing thrill for any film fan. I mean the man was starring in epics before I was born.

How important was the absence of the Greek gods in Troy?

It’s very important. It was part of the pitch from the get go. I really wanted to concentrate on the human aspect of the story. When Paris fights Menelaus in the book, it’s fairly similar to the way it is in the movie except at the end, when Paris is about to get killed, Aphrodite magically teleports him from the battlefield to Helen’s chamber in the palace. I just didn’t want it that way. I didn’t want to see the gods coming in and using magic to change the course of events. I really didn’t want to see an actor in a toga throwing CGI thunderbolts from the top of a CGI Mount Olympus because it becomes a much different movie. It really becomes much more about the effects and a magic kind of fantasy. I think the truly tragic, truly human element to this story is without the gods.

Was there more development to the story of Paris and Helen that we didn’t see onscreen?

Yes, there was, but it’s hard to tell this massive story. There’s not that much time, and inevitably, you’re going to lose some of the quiet time between characters. In the original myths, there’s much less, actually. Paris has to choose between three goddesses who are the most beautiful, and if he chooses Hera, she’ll make him the richest man in the world. I think if he chooses Athena, she’ll make him the wisest man in the world, and if he chooses Aphrodite, she’ll give him the most beautiful woman in the world. So Paris, being a man after my own heart, chooses Aphrodite, so Helen kind of magically falls in love with him, and I didn’t want to do it that way.

Now it’s this woman trapped in a loveless marriage. I mean she was forced to marry Menelaus. It was an arranged marriage as most royal weddings have been for thousands of years, and at 16 years of age, she’s forced into this marriage with this brutal warrior who she never really had any affection for. So in some ways it’s almost a fantasy of a love affair. Paris is rescuing her from what seems to be a loveless and sexless marriage. She tells him that she was ghost before he came to her.

Even though as a writer you always want to see all your scenes in the final movie, I think the movie works more powerfully at 2 hours 44 than at 3 and a half hours, which is what it would’ve been if everything had been shot. So on one hand I’m kind of like, “Oh, I really miss that scene,” but at the same time, looking at the larger picture, I think the movie works better without them.

To read the rest of this interview, plus other great content not available on the web, please subscribe to Screenwriter's Monthly, for just $15.95 you can get 6 months delivered to your doorstep.

More recent articles in Interviews

Only logged-in members can comment. You can log in or join today for free!

Advertisement